Why Governments Want a Piece of Apple

The Anti-Monopoly Case against Big Tech or why Apple is being sued

Hi, welcome to Dilemmas of Meaning, a journal at the intersection of philosophy, culture, and technology. I think that sometimes boring policy has a greater influence over our lives than we expect. Competition policy is one such thing. You can draw a line from the way we listen to music today to a court case against Microsoft more than two decades ago. So here I offer something of an explainer of what competition policy is, how it has failed (and created) the world of large tech corporation, and the European Union’s novel approach to fixing it.

There’s always a phrase or two associated with every brand that defines who they are. With Nike, it is “Just Do It”, L’Oréal tells you “Because You’re Worth It.” These phrases are truisms in that they tell you nothing beyond what is implied. But those with great marketing will imbue these slogans with meaning and exceptions beyond the catchy tagline. Apple Inc has a few, and through them you can tell a story of the largest corporation in the world, its relationship to its users and developers, and why the European Union is leading a new legislative rethink that has overturned more than a decade of company policy.

It just works. Repeated in keynote after keynote as the company announced devices, software, and services. It would be uttered right after a carefully choreographed feature was shown as if it were the simplest thing in the world. Again and again, the phrase functioned as a promise to their consumers, Apple was not going to be like those other computer companies with all the struggle and complexity, the random updates and hidden settings. To use an Apple product was to enter a world of ease.

To guarantee this promise, Apple demands a level of control unusual amongst computer companies. They make their devices to run their software preloaded with their apps. If you want more apps, you can go to their App Store. If you want to pay for that app, Apple handles the payment service. It is one seamless experience.

Another phrase to associate with Apple is vertical integration. It is the reason Apple gives for why their products just work. By controlling the hardware and the software—the entire chain—they can guarantee a specific user experience. However, the other side of the narrative is the truism of the walled garden one you will not hear in Apple’s highly produced keynotes but will be common amongst their developer community. By exercising a level of control, they become judge, jury, and executioner for anything happening on their products. It is beautiful inside their world—but make no mistake, it is their world.

Want to develop an app for an iPhone user? You’ll need to get a license from Apple. Want to distribute your app? You can only put it in their store. Want to make money from your app? You can only use their payment system (and pay their fee). Your app has been rejected by Apple? Guess who will be hearing your appeal. These conditions appear harsh and have led to predictions of an exodus of developers for greener, freer pastures. In a world where we are told to vote with our feet and wallets, why don’t developers leave? Unfortunately, the money and people are on the Apple App Store; iOS users are likelier to spend money than those on other platforms. To gain access to that market and to be able to make a living is to accept living within Apple’s world. For that, you must hand over all control and accept an imbalance of power.

That last point is where the Cupertino company finds comrades with other Silicon Valley giants. Many leaders in the digital economy—Meta or Google for example—enjoy an overwhelming leverage. Imagine advertising without Google or Facebook, or being an artist or creative without an Instagram page. These companies make their own rules and enforce it with neither check nor balance. For a developer/creator/business attempting to make a living in a world of digital marketplaces, is to accept working with a power imbalance. But to their users, it just works.

That’s the issue at play here. On one hand, us, the consumer, enjoying access to good, free, or low-cost services. On the other hand, business from a one woman developed app to Spotify, are at the mercy of the trillion-dollar corporations.

This is the challenge faced by those in government that seek to create a fair state of affairs. We have written in this journal about the tech industry and how that affects how we talk about new technological developments and how it affects identity formation. I would argue that what defines ‘tech’ as an identifier is less the use of technology, and more a collection of quirks that have made it an industry difficult to manage. Case in point, car companies use technology in both the making and within their products, but because they charge us for every vehicle, it is a lot easier to identify the problems with a lack of competition. Perhaps this theory is one the journal will return to later. Nonetheless, one quirk as illustrated in the above example, is the difficulty in applying competition policy and an unfair system is maintained.

Difficult but not impossible.

To understand the EU's Digital Markets Act (DMA) and why its enforcement is important, I’d like to offer a brief explanation of the current state of competition, why it has struggled to affect tech giants, and the new philosophy powering reform movements.

Since at least the Roman times, governments have acted to maintain fairness in business. From guilds to patents, tariffs to the price of grain. We call this competition. If you’d excuse this broad brush, competition policy agents the two largest drivers of global regulations—the USA and the European Union—have focused on us, the consumer. The problem with guilds and cartels and the price of grain is that the price. A lack of fair competition leads to prices going up. If you have no competition, you can be as greedy as you want. Operating under this belief, competition policy has seen as its trigger higher than acceptable prices. I’d draw you a chart, but this is getting long.

A more contemporary explanation might be a world where Cadbury's, the chocolatier, controls the entire chocolate market. They then slowly start to raise the price of their bars, slowly at first. As there are no alternatives, consumers are forced to bear the inflating prices. It is at this point that national governments would start talking about breaking up Cadbury's.

Let’s call this line of thinking, the consumer welfare model. Okay, that’s the status quo, why isn’t it working?

How much do you pay for an Instagram account? For access to the Apple App Store? To search for recipes on Google? The modern digital giant has grown on the back of free or low-cost services. Somewhere after guilds and grain, large corporations found a way to control markets without charging us much. Don’t mistake this for a change of heart, they haven’t read their Das Kapital and become born-again Communists. Rather than charging users more, they have looked to other businesses to make their profits.

Instagram and Facebook told businesses to find followers on their platform before turning around and charging to guarantee that those followers can see all their posts. Apple once rejected an email app because they did not include an in-app subscription purchase and avoiding the ~30% cut they take. This is why neither Netflix nor Spotify nor Amazon's Kindle apps allow you to sign up or pay within their iPhone apps. These are wealthy corporations who themselves have taken advantage of their economic power in other ways. Should we not then adopt the policy of 'let them fight', why should we care about Apple affecting Spotify for example?

We ought to care because of what proponents of a new school of competition policy calls the curse of bigness. Rather than a survival of the fittest amongst corporation levelling the playing field, the consequence of, say Apple affecting Spotify, is that the former grows larger. And with that size comes in-itself, problems. Apple, Google, and other large companies in Silicon Valley illegally conspired to keep wages low in addition to refraining from cross company poaching. This exemplifies the curse of bigness; because of their size, large companies are able to cover enough of the industry that their gravity affects wages. Such a thing could not happen in an industry with multiple corporations, the temptation to raise wages and break the cartel would be strong.

The curse of bigness is concerned about the effects of large corporation beyond the welfare of consumers as measured by costs. We live in an age of growing economic inequality and we are being increasingly aware of the problems private power poses to the economic and social conditions of democracies. Not to even mention the environmental impact large data centres have, as another example. The great hedge against this, beyond total economic revolution, is competition. If there are multiple alternatives in the world of business, we can minimise the consequences of the curse of bigness and look to guarantee that large corporations aid in delivering the common good. At least that’s the thinking.

This school of thought is novel, the first proponents in positions of serious power have been inaugurated within the last decade. The driver of competition policy is still consumer cost. Especially within the digital world.

If this was the case, it wouldn’t be revolutionary, bureaucracies have been changing names since the invention of language… and bureaucracy.

Things are finally changing. Within the last few years, the European Union has generated ideas for how digital marketplaces ought to work, racing ahead of the US, increasingly stuck within the framework of anti-competition judged primarily via the consumer welfare model. Among these, the DMA stands out. In part for its prescriptive rather than descriptive approach to competition and in part for being the one regulation to overturn 15 years of Apple history. Whether the regulations will lead to Arcadia, I will leave to the prognosticators and mystics. Instead, let's look at the changes it hopes to bring.

What is the DMA?

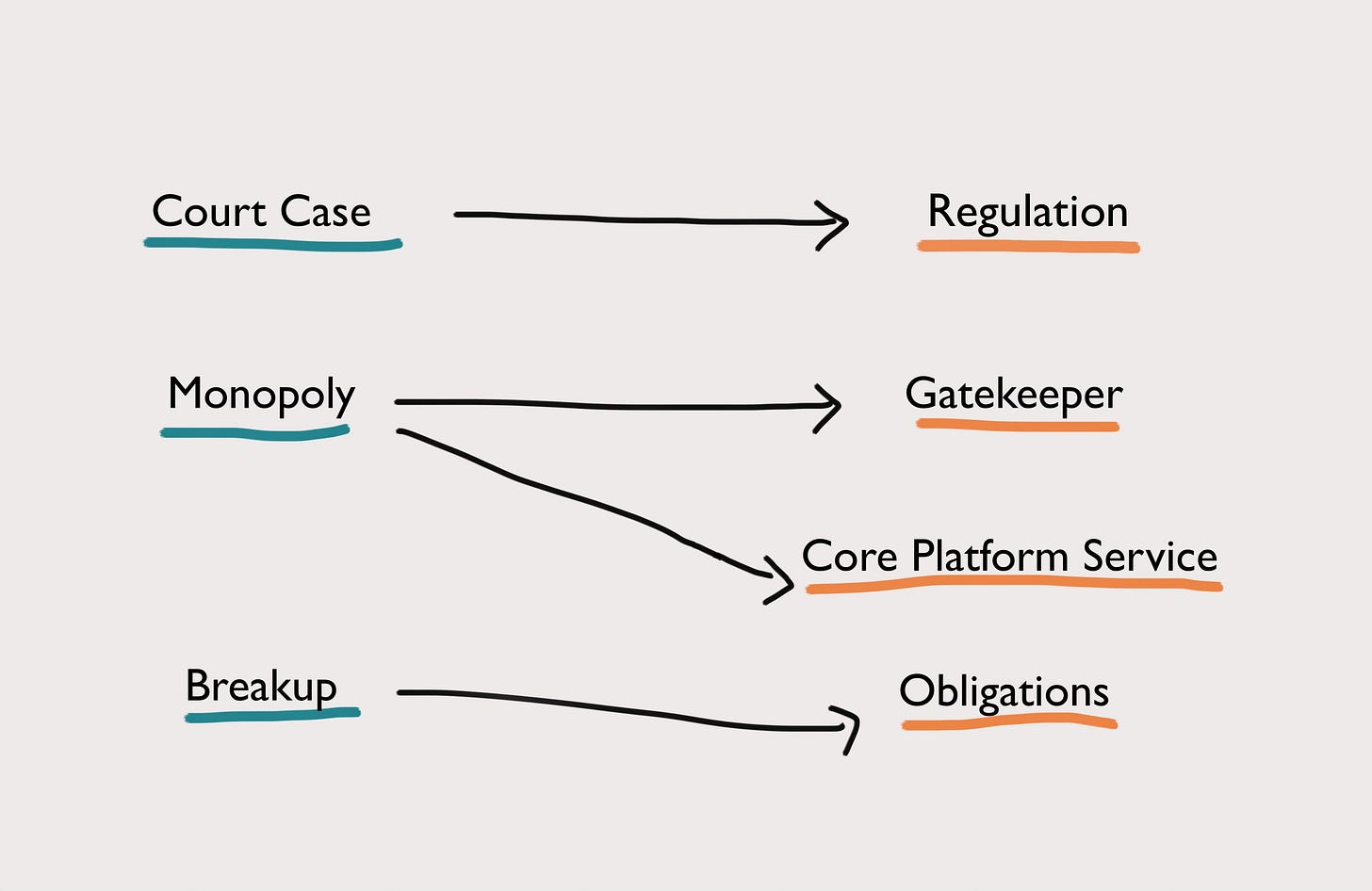

Under the DMA, the legal mechanism is a regulation rather than a court case. This means that rather than suing large corporations in a court of choice to prove they are monopolies, that those monopolies are bad, and relying on the courts to hand down a judgement (often breaking said large corporation), the DMA is an EU regulation.

These are the EU’s versions of laws that are immediately enforceable. It is faster and more uniform than a court case which must be brought for each large corporation.

Large tech companies rather than being deemed monopolies will be called Gatekeepers. The difference is that a monopoly is a description of the status quo. You look at the market, look at the effects, and decide whether there’s a monopoly or not. It is time consuming and difficult to prove. A Gatekeeper is value-neutral, it is a term prescribed by the EU Commission based on a few elements that are spelled out in legislation.

It allows more than price to factor in and captures more of the state of affairs. The argument is that Gatekeeper designation paints a fuller picture. If this was the case, it wouldn’t be revolutionary, bureaucracies have been changing names since the invention of language… and bureaucracy.

Gatekeepers do different things and not all of them require regulation. Bing is such an insignificant member of the search market that looking into it is more work than it’s worth. The Commission, therefore, picks certain services, video sharing, social networking, intermediaries, and anoints then Core Platform Service. It is these services that the Commission requires be good actors. Take the example of Apple (Gatekeeper). Everyone in Europe uses WhatsApp not iMessage so their Core Platform Service is their App Store, Browser, and iOS itself.

The final element of the DMA is the obligations enforced on large corporations. In a court case, the primary best case scenario for a monopoly case is the large corporation being broken up. This is such an extreme remedy that it is difficult to maintain after appeals. The DMA, rather than breaking up companies, works to ensure that their core platform services are open and fair to all. This might seem like a huge step back but the logic is that these obligations make for a fair market and vibrant competition. If you must keep your services fair, you are less able to use them to squeeze out potential competitors.

Of course, setting out to transform an area of tech policy is a ‘been there, done that’ for the EU. Watchers of Brussels are familiar with previous attempts such as the right to be forgotten, the move to one charging connector and GDPR; an experience that has ranged from fantastically successful to subjecting the world to a series of alerts to click I accept to banish them. Not content to be subject to new rules, Apple has been in the news not just for being forced to open up several services but maliciously complying with them, disregarding the spirit if not the letter of the law. I promised not to predict how this new era of competition policy will play out but whether the largest companies in the world play ball is not guaranteed.

The thing about those phrases I opened with is that they are rarely codified as mottos for corporations, but they can be more than marketing. When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in the late 90’s, he commissioned a new slogan, one that would reflect the philosophy that ought to be reinforced within the company. I’m sure you might have heard of it. I doubt the European Commission is auditioning advertising agencies as they seek to take on big tech but as they seek to break with decades of competition convention, they’ve had to be unorthodox—crazy even. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.1

Post script: Since working on this, the US Department of Justice has sued Apple for being an illegal monopoly. As the EU and USA embark on similar goals but with diverging methods, we have ourselves a natural experiment.