Why Coyote vs. Acme's Getting Cancelled

Why is Warner Bros Discovery Cancelling Movies and How did the Industry get this way

Hi, welcome to Dilemmas of Meaning, a journal at the intersection of philosophy, culture, and technology. I’m doing something different in this newsletter. Some who know me, know I have a tendency to fall down rabbit holes in trying to answer interesting questions. Here, in seeking to answer the question, how does Warner Bros. Discover get to cancel films for a tax write-off? I found myself deep in SEC fillings and reading some recent history. If you too are curious about the answer or want a deeper understanding on our current media landscape, enjoy.

The nineteen-month-old Warner Bros Discovery (WBD) is already losing money. Despite riding this summer's Barbenheimer phenomenon to break their own records, they've had to become financially creative. For a mass media and entertainment conglomerate, you might think the plan ought to be trying to release more profitable mass media and entertainment. However, WBD has gone for something simpler: they've removed releasing from the plan.

Earlier this month, word leaked that WBD would be shelving the unreleased film, Coyote vs ACME —taking a $30 million tax write-off. This marks the third film killed by the house that Jack (Warner) built for tax benefits after Batgirl and Scoob!:Holiday Haunt. Shelving films in progress is an unfortunate reality of the industry, but the implication that the work of many will never enjoy public consumption for a tax cut has caused uproar and disbelief. Coyote vs ACME is different. Allegedly, the film was both finished and good. Barbie, on its way to break records, started by replacing Coyote vs ACME in the summer schedule. A major movie studio has decided to take the tax savings from cancelling a finished film rather than enjoy the revenues it might generate.

In learning this news, I had two questions: how and why? I imagine many might have similar thoughts, so I did some digging and started writing.

How can Warner Bros. Discovery Cancel A Finished Film

First the how. The American tax system allows businesses to reduce their tax burden by deducting several costs from their taxable income. As a corporation formed via a merger, there are associated costs. Referred to in a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filing as Costs Associated with Exit or Disposal Activities. Part of those are content impairment and development write-offs. In English, WBD is able to take a look at content in development and decide, if as part of merging, they will need to cancel them for the sake of the merged company. The decisions of the past might not look so bright with new ownership. Since the accountants at WBD believe the ~$30 million tax deduction will be more than the profits made when considering addition costs, marketing, post-production etc, they shelved the release. As more time passes, fewer projects will predate the merger removing the tax benefits for cancelation. We hope.

Despite this, reactions to this cancelling have not been positive. Many who worked on the film and have shared what they can. Accounting practices and chequebook maths means that most of the good work poured into a creative endeavour will not be seen. This sentiment has animated the ensuing backlash and gets us towards the why.

New York Times Columnist, Jamelle Bouie, considered if making releasing the work into the public domain a condition for getting a tax write-off. I find this solution interesting; it paints this as a problem of profit versus art. Our present state speaks to the incentive structure leaning towards the former. If art is to be preserved, the logic goes, it ought to be released. Profit benefiting the small and the powerful, while art the common heritage of humankind. This framing centres WBD CEO David Zaslov.

There's the notion, built by puzzling decisions and maintained by unflattering profiles, that he exemplifies the profit over art approach. Marx remarks somewhere that men make history under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. I do not seek to exonerate Zaslov—he has better paid lawyers and publicists. Instead, I believe placing him, his company, and his actions within historical context reveals more about our media landscape. This goes beyond profit versus art. As the recently concluded writers and actors strike showed, media executives who put profit over art aren't rare in Hollywood. What makes this novel is the narrative of tech disruption; the perception that tech companies contain within them industry changing potential. It begins a decade ago, with a quote buried in a GQ profile and ends five years later. To understand what's happening now, we must return to the Golden Age of Netflix.

Sic Parvis Magna

In 2013, Netflix made more money from DVD distribution than online streaming. To call them a tech company would not be accurate. The next five years would radically transform the company and the media industry.

The goal is to become HBO faster than HBO can become us

So declared then Netflix Chief of Content and now Co-CEO Ted Serandos. At that point, Netflix had built a business distributing movies and TV shows they did not own. It was profitable, but it terrified them. Media companies saw Netflix as an afterthought, as a place to dump content after DVD sales plateaued and before it was syndicated for television. Netflix paid for this privilege but realised they had no leverage. To make matter worse, their success might encourage media companies to compete directly, cut out the intermediary, and stream directly to consumers.

There was desperation to go with ambition but make no mistake, they were being ambitious. HBO was the gold standard of television, in the premier tv awards show, The Primetime Emmys, they routinely cleaned up. In 2012, a year before Sarandos' declaration, HBO led both in nominations, 27, and wins, 6. To scale this peak, Netflix had a simple plan: work with big names, pay big, and pay upfront. Netflix sought to be the home of projects that had been turned down elsewhere but with enough cache to be prestigious. Rather than the normal television process of commissioning a pilot (a first episode), they would pay for an entire season. Trusting the celebrity creators and instead of playing producer, they'd stay out of the creative process. How then, would they ensure their shows would be worth their large costs? They would trust the data.

That last part is worth noting. Before TikTok enraptured the world with their recommendation algorithm, Netflix aimed to use their large user data to predict which shows might be popular. We know this because after securing the rights to a short British political show, a group including Academy Award nominated director David Fincher and (now disgraced) actor Kevin Spacey hoped to sign a deal with Netflix to syndicate the show after it finished airing. Instead, Netflix outbid some of the biggest names in American television for the show to be a Netflix original. Justifying the overpay, Sarandos pointed to a large audience overlap in their data between David Fincher, Kevin Spacey, and political thrillers. That emphasis on data guiding content, as well as Netflix streaming over the internet, helped paint them as more than a content company. They were tech, and that perception was everything.

Common to all, is the perception that they were tech companies and growth was their destiny.

How did the plan work? Better than anybody could have predicted. 2013-2018 could be considered the golden age of Netflix original content, buoyed by hits: House of Cards, Orange is the New Black, Narcos, Ozark, Stranger Things and The Crown to name a few. Netflix became an Emmy’s regular, picking up nominations and a few awards each year until their peak at the 70th edition in 2018: Netflix finally led HBO both in nominations, 37 to 29, and wins, 7 to 6. They had achieved the first half of Sarandos’ challenge. As for the second? HBO Go was the closest equivalent to Netflix launched in 2010. It allowed consumers to stream HBO shows over the internet. Unlike Netflix, however, it was linked to an expensive cable subscription package (meaning you could not pay for it on its own) and plagued by outages. Netflix had cemented itself as the streaming platform and nobody could keep up.

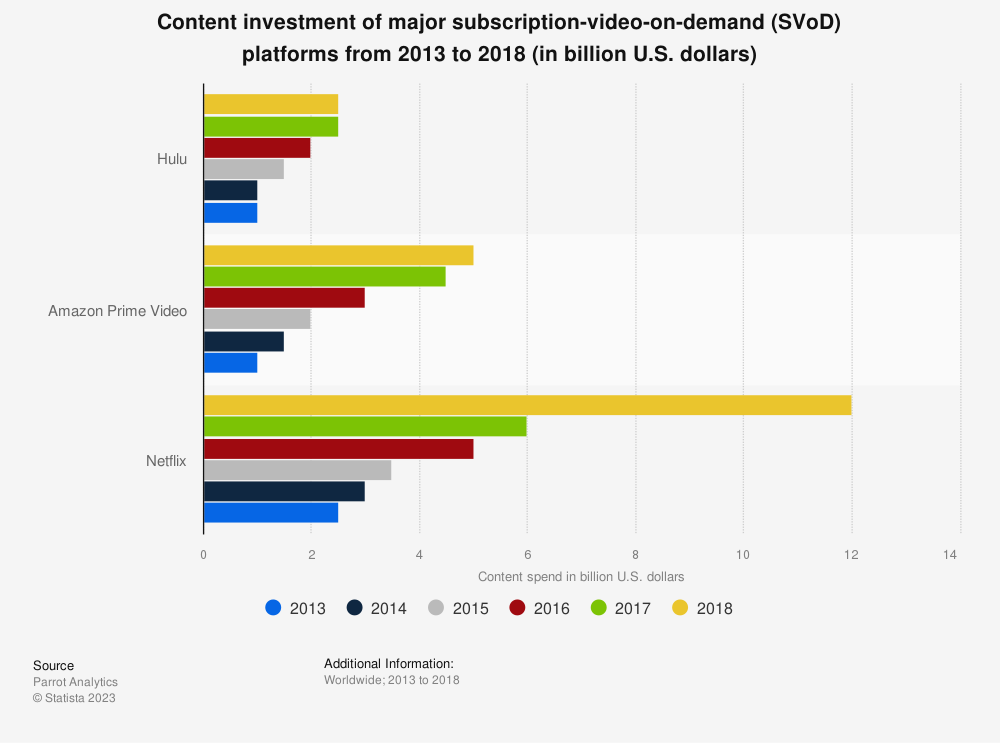

This success did not come cheap. Compared to other streaming services, Netflix outspent its closest competitors:

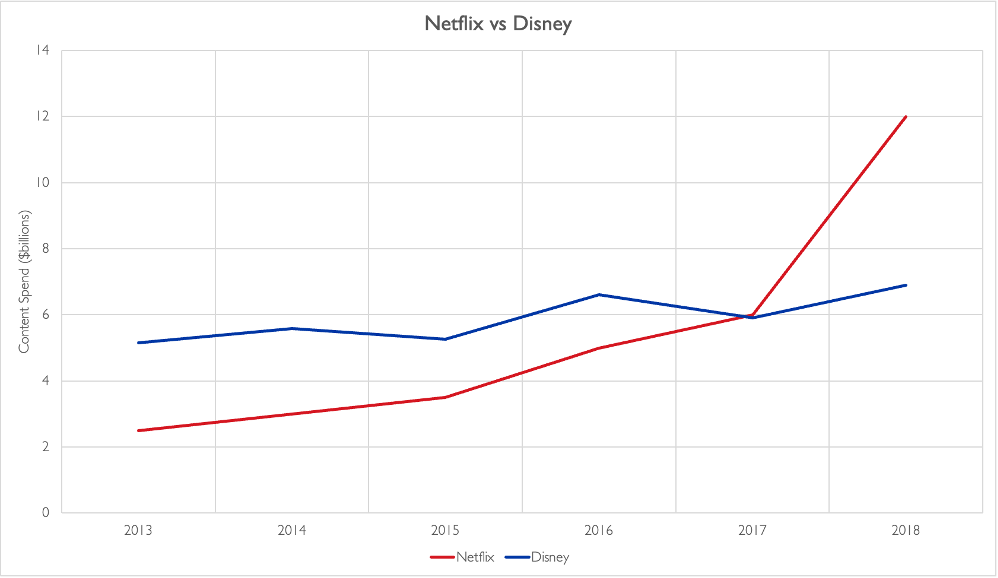

More instructive might be placing Netflix’s content spending placed next to Walt Disney Studios. Disney, at this point, was at beginning of the Marvel and Star Wars boom, necessitating large spending on blockbuster franchises:

Netflix keeps up until it begins ramping up from 2016 onwards, reaching the astronomical figure of $12 billion in 2018. This spending might be money well spent, growing their subscriber count from 41.43 million in 2013 to 139.26 million in 2018. Did they make money? Abso-fuckin-lutely. Revenue went up from $4 billion to $15 billion. Disney in comparison went from ~$6 billion to ~$10 billion in the same time frame. These numbers are real, people worked and were paid, were hired and fired based on these numbers. But as public companies, important is how the financial markets perceived both companies.

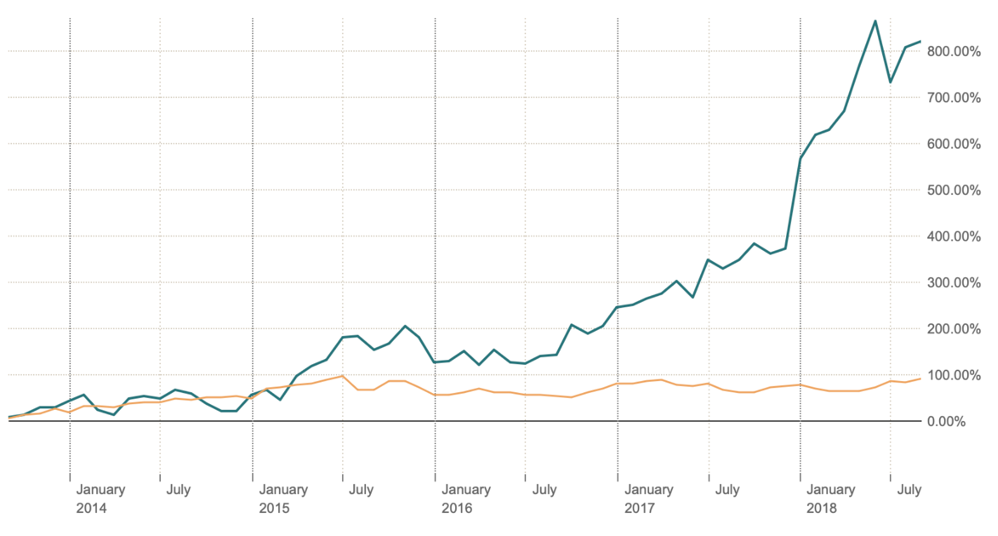

For the same time, here’s how their stocks performed:

From a comparable start, Netflix rose to finishing at a stock price eight times that of Disney. The important thing is not the price; Disney pays out dividends (making the stock attractive not just for growth) and trades a greater volume of shares. Instead, it’s the trajectory of Netflix’s stock price, one that doesn’t resemble a conventional media company but a tech one. Spending a lot of money to capture a market share with few players? Your line will go up. It is this phenomenon that got CNBC’s Jim Cramer to coin the acronym FAANG, grouping together Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google. Common to all, is the perception that they were tech companies and growth was their destiny.

In 2013, Netflix was a content distributor, sending out DVDs and letting you stream other companies’ movies and shows. by 2018, they were merging technology and media into a package Wall Street loved. Eager to capture the same zest, media companies began transforming themselves to walk and talk like tech companies. Disney began acquiring BAMTech, a streaming technology business, in 2016 finishing in 2018. Disney+ would launch a few years later. As Netflix worked to cement their hold on the streaming market, the Trump administration approved a purchase by AT&T, a company with a lot of technology, for Time Warner, a company with a lot of media. A lot of media that included both Warner Bros Studio and HBO.

By bringing an historic media company under the auspices of AT&T, Warner Bros’ priorities would change. Rather than being a place to make and release movies and award winning television, the suits at the top began trying to turn them into a chimera chasing the kind of growth Netflix enjoyed. It is not quite profit vs art, but transforming the business of media from one that earns from its releases to a tool to capture the hype and potential tech products endear. The plan was no longer to make money the traditional way. Lines could go up.

Keen readers will realise this is a history cut short. We end with Warner Bros part of, I assure you, one of the worst mergers in recent history. I think it is an important story to tell but I both take a while to research and would rather not find out the Substack word count. So let’s split the difference and come back in a few weeks for the second part. As always, thank you for reading. Till next time.

Sic Transit Gloria Media